Reading this book was an interesting experience.

My dad is a pretty devoted Wilberian. It would perhaps not be far from the mark to say that "wilberism" was the religion that I grew up in. For this reason, the strangest thing about reading this book was realizing how profoundly I had been influenced by Wilber's system.

The other strange thing was the contrast between how much I liked the first half and how much I disliked the second. I'll return to this in a second, although the details of our disagreement are too technical for a blog post.

(I do however find Wilber's aesthetics to be a bit questionable. He gets into bestselling cult-leader territory, and he has horrible taste in art. He uses too many words with capital letters, and is more in bed with the New Agers than he would like to admit.)

The basic project of this book, which was published in 1996 as a response to the rather dogmatic deconstructionism that was (and still is) the current theoretical orthodoxy in academia.

Wilber here attempts to devise a synthesis of rationality (coded: western) and mysticism (coded: eastern). The elegant theoretical structure with which he describes the internal dynamics of intellectual history is impressive, and, as I said, my own thought is as indebted to Wilber as it is to my other touchstones like Jameson or Harvey. His elaboration of this structure takes up the first half of the book. Wilber's thought here is presented with a clarity that is admirable; It is perfectly accessible to a lay person and for somebody with a background in theory it is quite easy.

An attempted sketch of Wilber's arguments (and I am in substantial agreement with all of these positions - but I would draw my picture a little bit differently):

The metaphysical structure of the entire universe is the holon, which is a whole that is also a part of some higher structure. For example, oxygen atoms are wholes, but they are parts of water molecules. I am a whole, but I am a part of my society. Everything is like this. In fact, the entire universe is an enormous "holarchy" composed of progressively higher levels of organization.

All holons can only be fully understood through a consideration of their manifestations in four "Quadrants:" upper left, lower left, upper right, and lower right. Essentially, these are four different viewpoints on the same phenomena. The universe is thus a great holarchy which is unfolding simultaneously through the four quadrants. The right hand side is the objective side, while the left hand side is the subjective side; the top is singular, the bottom is plural. Furthermore, the quadrants can be mapped onto the grammatical pronouns in the following way; upper left is I, lower left is We, upper right is It, and lower right is Its.

So if we want to understand, for example, consciousness, we need to understand it from all of these perspectives. The upper left is the individual subjective, or psychological development. The lower left is culture, or the collective subjective. The upper right is the individual objective, the development of the brain. The lower right is the collective objective, the systems of political and social organization.

Holons evolve through these quadrants in a process that is essentially a Hegelian dialectic. Wilber stresses the phrase "transcend and include," which means that each higher holon contains all of the structure of its parts, plus more.

As the major purpose of this book is to understand the evolution of culture, or the development of our collective worldview, this idea of transcendence and inclusion means that, in order to be healthy, a new worldview must embrace the truths of the worldview it has replaced. As Freud discovered, repression leads to pathology. Therefore, if a new worldview (e.g. the Rational of the Enlightenment) represses rather than includes it predecessor (the Mythic of the feudal period) then it becomes pathological. This, Wilber argues, is the origin of the deconstructive turn in postmodernity.

Essentially, Wilber thinks that all of western philosophy since Plato has been an attempt to reduce on half of the quadrants to the other. That is, to show that everything objective was only subjective, or to show that everything subjective was only objective. The current pathology he terms "flatland" which is the reduction of the right hand quadrants to the left hand quadrants - basically to show that all subjective consciousness is "nothing but" the activity of neurons, etc. His solution to this is that Western science and Eastern spirituality need to team up, and then everything will be great.

This is the first half of his book, and he's mostly totally right. The second half is a polemic against a poorly argued straw man he calls "subtle reductionism." As the blog is getting a bit long I won't go into the details, but the short version is that I myself am a "subtle reductionist," and I think Wilber does not fully appreciate most sophisticated version of this position. I think that he does not understand the full philosophical implications of emergence, complexity, and evolutionary dynamics, and I think his mistakes here make the second half of the book moot.

TL;DR:

So, I guess, I would highly recommend the first seven chapters of this book. In it, he presents the most complete and elegant comprehensive philosophical theory I have encountered. After that, he makes a crippling mistake and takes a tangent off into orbit.

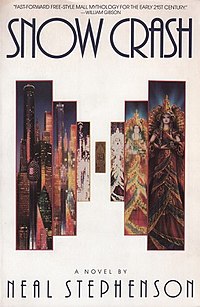

PS Sorry, Brack, I only read these very serious books these days. But there is an absurdist science fiction novel on the way (secretly though Very Serious) and also the Analects of Confucius, which is exquisite.