Hey everybody

I'm going to be maintaining a list of recommended reading on my website. It's not finished just yet but I thought it might be of some interest. Cheers

http://colindrumm.com/recommended-reading/

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Monday, February 27, 2012

Ryu Mitsuse - 10 Billion Days & 100 Billion Nights

This book is utterly insane, and operates under the principle that sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, mystical experience, or a really incredible psychedelic voyage.

At one point, Jesus of Nazareth and Siddhartha Guatama the Buddha, who are cyborgs, fight a laser battle amidst the fortieth-century ruins of Tokyo. I feel like that should be recommendation enough. If dream narratives aren't your thing, though, you might find the book frustrating.

The story is a sort of metaphysical space-opera with Dickian gnostic overtones, featuring Plato, Jesus, Buddha, and the goddess Asura. The translation is excellent and highly poetic; the original Japanese must be pretty amazing.

Labels:

artifical intelligence,

Buddha,

Colin,

cyberpunk,

fiction,

futuristic,

Japan,

magic,

metaphysics,

Plato,

religion,

sci-fi,

science,

technology,

Tokyo,

war

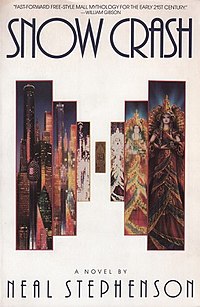

Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash

Stephenson has rapidly become one of my very favorite, if not all time favorite, authors. Snow Crash is so incredible - Stephenson's vision of the future is a rarity in its clarity, depth, and originality. The overpopulated earth has become a trashy wasteland, and the technological/economic elite have essentially moved to a digital existence, most often "goggled in" to the virtual reality of the Metaverse, where your avatar can move around and conduct business in the same way as on earth. Hackers, especially the samurai-sword wielding protagonist (named Hiro Protagonist), have the upper hand in a landscape they can control. However, the intersection between man and machine, embodied particularly in the hackers' binary-acccomodating neural pathways, has led to the dangerous potential for computer viruses to infect the user's mind. This unique vision has even more resonance given Google's recent announcement that they are developing glasses which will project a virtual reality and other information over the real world. This novel's astounding scope encompasses the exploration of memes, Glossolalia, drugs, viruses, and religion, which are depicted as being basically synonymous. A wonderful page-turner!

Monday, February 20, 2012

Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time

Since I have recently been pursuing the fundamental philosophical question "why is there something instead of nothing" from one end of the philosophical tradition, Daoist metaphysics in particular, I decided to switch gears for a bit and see what professor Hawking had to say about the issue.

A Brief History of Time is an eminently accessible guided tour, not through time itself, but through the Western tradition's understanding of the nature of the universe. Hawking walks the reader through the major paradigm shifts in intellectual history, beginning with the Copernican revolution, and explains in each case why the previous theory had to be abandoned and why the new one was chosen. The first section of the book should be familiar to most readers from high school. The second half was all things I had heard of before, and understood to some extent, but quantum mechanics et al. are always worth thinking about again.

Hawking presents the history of cosmology as the gradual reconciliation and elaboration of partial theories, with the current problem in physics understood as the production of a theory that will unify quantum mechanics and general relativity; in other words, reconcile our theories about what happens at very small scales and very large ones, respectively. Reading this book makes me nostalgic for the alternate life in which I pursued mathematics and understood in something more than a qualitative way what was at stake in all of this, but Hawking generously includes the rest of us in the conversation with his clear presentation.

The best part of the book, by far, is Hawking's stories about the bets he has made with various physicists on points of theoretical contention.

"I... believe there are grounds for cautious optimism that we may now be near the end of the search for the ultimate laws of nature."

Labels:

Colin,

Copernican revolution,

cosmology,

Daoism,

history,

nonfiction,

philosophy,

Stephen Hawking,

theory

Sunday, February 19, 2012

John Brunner - Stand on Zanzibar

Another classic science fiction novel that I never knew existed. Written in 1968, Stand on Zanzibar is set in a crowded, decolonized early 21st century. The world is filled with mass-market psychedelics and eugenic legislation, overstimulated and disney-fied in a way that hits pretty close to home. The world's crowded cities are terrorized by "muckers," or people driven to the point of berzerk killing sprees. Brunner's vision is on the level of a Philip K. Dick in terms of sheer affectual prescience.

The novel contains several narrative threads, interspersed with commercials and other snippets from the infosphere, as well as vignettes that act as character sketches of various dysfunctional relationships (usually centered around attempts to circumvent eugenics laws). Other sections are polemics, written in the voice of Chad Mulligan, who can perhaps best be described as stand up comedian channeling Vonnegut.

The two main plot lines involve a propaganda campaign by a Southeast Asian archipelago claiming that they will genetically modify their next generation to breed a perfect species, and a series of negotiations between a large US corporation and a small African ex-colony which is mysteriously free of violence, and whose people have had a reputation for witchcraft stretching back into prehistory.

The novel is scathing and quite funny. I find most satire to be a bit cringe-inducing, but Brunner pulls off his tone with an aplomb that reminds me most of David Foster Wallace.

Labels:

Africa,

Colin,

drug culture,

dystopia,

fiction,

humor,

John Brunner,

post-apocalyptic,

propadana,

satire,

sci-fi,

social commentary

Paul Gilding - The Great Disruption

There is a war coming.

In this book, Gilding tries to articulate a way out of the mess we're in - he says, in essence, "if we're going to solve these problems, here's what it will look like." He argues that the coming crisis will initiate a response from the first world directly analogous to that of the second world war, in which enormous swaths of first world economy were nationalized and repurposed to the war effort. It is this wartime economy, with an emphasis on efficiency and frugality, that will allow us to orchestrate a crisis management response to the collapse that we are now far too late to head off with more gradual efforts.

While much of the material covered in the book is not new to me, Gilding's experience as first an environmental activist with Greenpeace, and later as a environmental consultant who has worked with people like the CEO of DuPont, provides a perspective that is more of an insider's view.

I think the most important point that I drew from this book was his argument that we cannot fight a war on two fronts. The first front is the radical and transformative restructuring of our political and economic systems that will allow the creation of a sustainable and steady-state (as opposed to growth-focused) economy. The second is the direct response to the chaos and violence that will make the conflict of the twentieth century look like a gentlemanly session of fisticuffs. Since the vested interests of the current establishment will, like any hegemony, fight to protect its power, we need to find a way to in the short term harness the old capitalist system to fight the Carbon War, in a concerted effort that will in turn bring about the systemic transformation that we need so desperately.

While I don't know if I share Gilding's optimism, his analogy to the war-time effort of WWII is thought provoking (he notes that military spending went from 3 percent of GDP at the beginning of the war to 39 percent at the end, in a time when the GDP as a whole increased by 75 percent.) If we can accomplish something similar, along with a total paradigm shift in the consciousness of the first world which will divert our collective activity away from mindless consumption, there may still be hope.

Saturday, February 18, 2012

The Anubis Gates

... Wow. Where to begin with this book?

... Wow. Where to begin with this book?

Okay, this is a book in the fantasy genre that, in some circles, I believe, has been sourced as an inspiration for steampunk novels, which I have yet to read. Honestly, I'm not sure why, because it had little to do with steampunk, but it had a sort of science fiction element in regards to time travel, and the rest is just straight fantasy.

"Just straight fantasy", however, can barely begin to describe the scope of this book. The story is so masterful and creative that it blew my mind. The basic idea is that a bunch of Egyptian warlocks are using their magic to change the past, thereby assuring Egypt's supremacy in the world. Our hero is Brendan Doyle, a modern expert on Coleridge, who travels to the past so as to attend one of Coleridge's lectures, but by the screwy nature of fate, he gets captured and is stuck in the past. The stories collide, and all hell breaks loose.

Again, I cannot describe just how awesome the story is. The plot devices are magnificent, the writing is great, the characters are amusing and engaging, and the extranormal aspets of the story are explained well and keep consistent with themselves throughout.

I highly recommend this book to anyone who is at all interested in fantasy, or history, or even a little science fiction. Seriously. READ IT!

Labels:

Egypt,

fantasy,

fiction,

history,

magic,

sci-fi,

steampunk,

Tim Powers,

time-travel,

Will

The Power of Full Engagement

Another in my slew of self-improvement books comes "The Power of Full Engagement". This particular one focuses on the idea that one should budget their energy, not their time, so as to achieve maximum productivity.

Another in my slew of self-improvement books comes "The Power of Full Engagement". This particular one focuses on the idea that one should budget their energy, not their time, so as to achieve maximum productivity.

The book was quite good, in my opinion, as it offered information that normally doesn't get tossed around in self-improvement circles as much. The only complaint I would voice against the book is that it was too long for the information imparted. The system they gave towards working on one's life, in my opinion, was quite good, but because of this, I felt the book lacked focus, considering it could have summed up the core message in about a hundred pages.

Nonetheless, I think that the book is a good primer on the subject, and I'd recommend reading it to up the simplicity of your life.

Labels:

inspirational,

nonfiction,

practical advice,

self-help,

Will

Friday, February 17, 2012

Thomas Cleary - The Essential Confucius

This is the best book I have ever read.

Cleary's translation is extremely readable - his ordering is somewhat unorthodox but I don't understand what the details of that are.

As for the text itself, nothing has ever struck me so deeply. I have read the Analects before, but I did not fully appreciate it. I think everyone should study this book carefully and live their life by it. I am not going to say anything else about it because it is very short and the master speaks for himself.

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

Ken Wilber - Sex, Ecology, Spirituality

Reading this book was an interesting experience.

My dad is a pretty devoted Wilberian. It would perhaps not be far from the mark to say that "wilberism" was the religion that I grew up in. For this reason, the strangest thing about reading this book was realizing how profoundly I had been influenced by Wilber's system.

The other strange thing was the contrast between how much I liked the first half and how much I disliked the second. I'll return to this in a second, although the details of our disagreement are too technical for a blog post.

(I do however find Wilber's aesthetics to be a bit questionable. He gets into bestselling cult-leader territory, and he has horrible taste in art. He uses too many words with capital letters, and is more in bed with the New Agers than he would like to admit.)

The basic project of this book, which was published in 1996 as a response to the rather dogmatic deconstructionism that was (and still is) the current theoretical orthodoxy in academia.

Wilber here attempts to devise a synthesis of rationality (coded: western) and mysticism (coded: eastern). The elegant theoretical structure with which he describes the internal dynamics of intellectual history is impressive, and, as I said, my own thought is as indebted to Wilber as it is to my other touchstones like Jameson or Harvey. His elaboration of this structure takes up the first half of the book. Wilber's thought here is presented with a clarity that is admirable; It is perfectly accessible to a lay person and for somebody with a background in theory it is quite easy.

An attempted sketch of Wilber's arguments (and I am in substantial agreement with all of these positions - but I would draw my picture a little bit differently):

The metaphysical structure of the entire universe is the holon, which is a whole that is also a part of some higher structure. For example, oxygen atoms are wholes, but they are parts of water molecules. I am a whole, but I am a part of my society. Everything is like this. In fact, the entire universe is an enormous "holarchy" composed of progressively higher levels of organization.

All holons can only be fully understood through a consideration of their manifestations in four "Quadrants:" upper left, lower left, upper right, and lower right. Essentially, these are four different viewpoints on the same phenomena. The universe is thus a great holarchy which is unfolding simultaneously through the four quadrants. The right hand side is the objective side, while the left hand side is the subjective side; the top is singular, the bottom is plural. Furthermore, the quadrants can be mapped onto the grammatical pronouns in the following way; upper left is I, lower left is We, upper right is It, and lower right is Its.

So if we want to understand, for example, consciousness, we need to understand it from all of these perspectives. The upper left is the individual subjective, or psychological development. The lower left is culture, or the collective subjective. The upper right is the individual objective, the development of the brain. The lower right is the collective objective, the systems of political and social organization.

Holons evolve through these quadrants in a process that is essentially a Hegelian dialectic. Wilber stresses the phrase "transcend and include," which means that each higher holon contains all of the structure of its parts, plus more.

As the major purpose of this book is to understand the evolution of culture, or the development of our collective worldview, this idea of transcendence and inclusion means that, in order to be healthy, a new worldview must embrace the truths of the worldview it has replaced. As Freud discovered, repression leads to pathology. Therefore, if a new worldview (e.g. the Rational of the Enlightenment) represses rather than includes it predecessor (the Mythic of the feudal period) then it becomes pathological. This, Wilber argues, is the origin of the deconstructive turn in postmodernity.

Essentially, Wilber thinks that all of western philosophy since Plato has been an attempt to reduce on half of the quadrants to the other. That is, to show that everything objective was only subjective, or to show that everything subjective was only objective. The current pathology he terms "flatland" which is the reduction of the right hand quadrants to the left hand quadrants - basically to show that all subjective consciousness is "nothing but" the activity of neurons, etc. His solution to this is that Western science and Eastern spirituality need to team up, and then everything will be great.

This is the first half of his book, and he's mostly totally right. The second half is a polemic against a poorly argued straw man he calls "subtle reductionism." As the blog is getting a bit long I won't go into the details, but the short version is that I myself am a "subtle reductionist," and I think Wilber does not fully appreciate most sophisticated version of this position. I think that he does not understand the full philosophical implications of emergence, complexity, and evolutionary dynamics, and I think his mistakes here make the second half of the book moot.

TL;DR:

So, I guess, I would highly recommend the first seven chapters of this book. In it, he presents the most complete and elegant comprehensive philosophical theory I have encountered. After that, he makes a crippling mistake and takes a tangent off into orbit.

PS Sorry, Brack, I only read these very serious books these days. But there is an absurdist science fiction novel on the way (secretly though Very Serious) and also the Analects of Confucius, which is exquisite.

Labels:

Colin,

cosmology,

evolution of culture,

Hegel,

Ken Wilber,

metaphysics,

mysticism,

nonfiction,

Plato,

postmodernity,

psychology,

rationality,

theory

Thursday, February 9, 2012

The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism

So I was researching into presidential candidates, and in the debate, I found that "American Exceptionalism" was mentioned multiple times. While I found basic definitions online, I found this book mentioned a few times, and thought that it might help teach me exactly what everyone was so hyped up about.

So I was researching into presidential candidates, and in the debate, I found that "American Exceptionalism" was mentioned multiple times. While I found basic definitions online, I found this book mentioned a few times, and thought that it might help teach me exactly what everyone was so hyped up about.

So, "American Exceptionalism" is the concept that America is a special nation, as first mentioned by de Tocqueville after a visit here. The term has transformed, until now, it refers to how America believes that it can justify its actions simply by dint of its "exceptionalism", and ignore the consequences as less exceptional nations cannot.

The book's premise is that America was founded upon principles of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, and as admirable as this is, our pursuit of them in the modern day has stretched too far in three spheres: political, economic, and militaristic. The book goes through the three areas, giving the history of how we arrived at the current conditions in said area, and how we are pushing the limits of power.

The book, I thought, was very good in that it was very well-researched and made a great many points, but my difficulty with it is that I can't tell its actual purpose. The author lambasts the entirety of the U.S., and so alienates anyone he might be persuading. If the book is just to inform, it's quite interesting, but in that case, why the acerbic tone? As such, I think the book fails to accomplish whatever purpose it was intended for, but it was still a very interesting read. I recommend it to those interested in U.S. politics.

P.S. This guy has a love relationship with Reinhold Niebuhr, a well-known theologian whom I had to read last semester for my religion class.

Labels:

America,

evolution of culture,

history,

politics,

power,

Reinhold Nieburhr,

theology,

theory,

Will

Saturday, February 4, 2012

The Stars Look Down

This novel, by Scottish physician and author AJ Cronin, is a powerful and emotional account of the plight of coal miners in Wales, interweaved with moving stories of struggles between people with different values.

The story begins cruelly with the miners returning to work after a lengthy and unsuccessful strike that has caused substantial hardship, to the point of desperate hunger. Robert Fenwick led the strike to obtain changes he felt essential for the miners' safety, but is now scorned by the miners and his own wife. Inevitably, the disaster he foresaw does occur: the miners break through a barrier into an underground reservoir, flooding the mine. Over 80 miners are quickly drowned, while Robert, with controlled intelligence and courage, leads his son Hughie and 10 others to safety into an old portion of the mine. They become trapped, however, by tons of collapsed tunnel and must wait for rescue. As days pass, first lit by candlelight and eventually in darkness, the miners die one by one. The account of the deaths by drowning, though short, is vivid and chilling; the drawn out description of the deaths of the trapped miners is harrowing.

Over the next decades, the story reveals the effects of this disaster on Robert's idealistic son Davey, on Arthur, the tortured son of the domineering and rapacious mine owner, and on Joe Gowlan, who flees the mines to become a successful and powerful war-profiteer. SPOILERS: Davey fights for miners' rights by striving to promote nationalization of the mines. Eventually elected to Parliament, Davey becomes a prominent miners' advocate, but the crushing realities of politics as usual and the influence of well-heeled capitalists defeat his efforts. After his father is debilitated by a stroke, Arthur uses the mine's astonishing war profits to initiate massive improvements. Crushingly, his outlays, coupled with economic downturn, lead him to the brink of bankruptcy, while his perceived weakness and the disregard for miners shown by politicians and other mine owners, make him an object of scorn rather than appreciation among the miners. The despicable Gowlan succeeds in business beyond his wildest dreams, makes massive amounts of money during the war, and eventually defeats Davey's attempt to be re-elected to Parliament.

Written in 1935, the book expresses a view of capitalism that resonates with present conditions:

The story begins cruelly with the miners returning to work after a lengthy and unsuccessful strike that has caused substantial hardship, to the point of desperate hunger. Robert Fenwick led the strike to obtain changes he felt essential for the miners' safety, but is now scorned by the miners and his own wife. Inevitably, the disaster he foresaw does occur: the miners break through a barrier into an underground reservoir, flooding the mine. Over 80 miners are quickly drowned, while Robert, with controlled intelligence and courage, leads his son Hughie and 10 others to safety into an old portion of the mine. They become trapped, however, by tons of collapsed tunnel and must wait for rescue. As days pass, first lit by candlelight and eventually in darkness, the miners die one by one. The account of the deaths by drowning, though short, is vivid and chilling; the drawn out description of the deaths of the trapped miners is harrowing.

Over the next decades, the story reveals the effects of this disaster on Robert's idealistic son Davey, on Arthur, the tortured son of the domineering and rapacious mine owner, and on Joe Gowlan, who flees the mines to become a successful and powerful war-profiteer. SPOILERS: Davey fights for miners' rights by striving to promote nationalization of the mines. Eventually elected to Parliament, Davey becomes a prominent miners' advocate, but the crushing realities of politics as usual and the influence of well-heeled capitalists defeat his efforts. After his father is debilitated by a stroke, Arthur uses the mine's astonishing war profits to initiate massive improvements. Crushingly, his outlays, coupled with economic downturn, lead him to the brink of bankruptcy, while his perceived weakness and the disregard for miners shown by politicians and other mine owners, make him an object of scorn rather than appreciation among the miners. The despicable Gowlan succeeds in business beyond his wildest dreams, makes massive amounts of money during the war, and eventually defeats Davey's attempt to be re-elected to Parliament.

Written in 1935, the book expresses a view of capitalism that resonates with present conditions:

At last, through their constitutional hidebound apathy, people were beginning to question the soundness of a political and economic system which left want, misery and unemployment unrelieved. New and bold ideas went into circulation. Men no longer retreated in terror from the suggestion that capitalism, as a system of life, had failed.At book's end, both Davey and Arthur are back in the mines, working under Gowlan. Jeez, this sounds depressing! The fundamental inequalities and unfairness of British society depicted here are leavened, however, by the rich interpersonal relationships, which provide many heart-warming and heart-rending incidents. Moreover, Davey convincingly achieves individual fulfillment, even as his professional ambitions are thwarted, and the book ends on an optimistic note. Very highly recommended!

Labels:

capitalism,

coal mining,

depressing,

drama,

fiction,

social commentary

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)